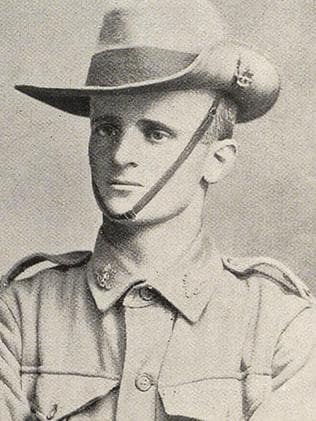

Lt William Vivian Keats 263

Lt William Vivian Keats grew up in South Hobart and on enlistment still lived with the family at MacRobies Gully. He was educated at Macquarie State School, now South Hobart Primary School. He enlisted on September 9th 1914 and was described as 5 ft 6 ½ ins in height with a dark complexion, dark brown hair and blue eyes. He was 24 years and 9 months in age and worked as a clerk at the Hobart Savings Bank. He was promoted to Lance Corporal on February 9th 1915, to Corporal on August 4th 1915 and Sergeant on December 1st.

This letter was written while on sick leave having been wounded on April 25th on Gallipoli to which he returned on July 18th. His account of events can be confirmed by reading L M Newtown The Story of the Twelfth Hobart 1925 pp43-46; Newton was an officer in B Company and relates the same story of the landing, climb and shellfire on the plateau.

“Base Details”

Zeitoun

19/6/1915

Dearest Mother and Dad

Have just settled down to send you a few lines re our landing etc. One of the chaps here received a few Australian papers, and I see by them that you have had a fair amount of same, still I will endeavour to give you a short account. My time is limited, so will ask you to please excuse me if I am a trifle briefer that I would have been had I plenty of time.

Since I arrived here I have been very busy, and now they have given me a section to look after, and that alone will keep me on the move. As I was unable to write to you about our late movements at Mena, I will start from there and briefly lead up to what took place on that memorable Sunday morning. We were rushed away from Mean, not that we were sorry to leave, but I would have liked to have been able to let you know. At 4.30pm on the last day of February (Sunday also), we lined up, and it was not long before Mena Camp was lost to the men of the 3rd Brigade. It was a very solid march to Cairo, the hard roads gave some of the me a rough passage. Cairo was reached about 8.30pm, entrained and left at 11pm, arrived at Alexandria next morning just as it was breaking dawn, and embarked on the “Devanah.” next morning (Tuesday), the “Devanah” steamed out, destination unknown. A couple of days after, we anchored in harbour at Lemnos Island. We fully expected to have gone into action in a couple of days, but weeks went by and still we did not move or appear likely to do so, and all began wondering if we were going to see any fighting after all. During our stay at Lemnos, some very solid work was gone through; we did not leave the transport, the men had to row themselves, or rather their mates ashore, it was fine exercise and kept them in fine condition. It was not until the middle of April that anything like “biz” began to put in an appearance, and we were issued with tow days emergency rations, bully beef and biscuits. The next few days were practically occupied with lectures etc. “B” coy. were the first to leave the “Devanah”, and on Monday morning there was quite a stir when the trawler came alongside to take us off. We all tipped going on to a Destroyer, but after about half an hour’s run, the trawler put alongside the “Ionian.” Day after day went by, and each day it was to be told that we were leaving for the Dardanelles next day, and were just beginning to expect a few weeks on her, and I can tell you that we did not want it, for she wasn’t a fit boat to keep pigs, let alone troops, on. Friday things began to hum, and continued all day Saturday, and by 6 o’clock that night everything was ready. It was a great sight to see the transports, accompanied by Destroyers, Cruisers etc., chasing each other at regular intervals. Our transport left at 2.30pm Saturday afternoon, and as I said before, all were prepared for action by 6pm. All ports were blocked up that night, for it was essential that no lights should be visible from the outside. Everyone was in their glory and eager to get going. The men mostly adjourned to the troop decks and had a good old “grand finale”, singing the latest patriotic songs etc., others discussed all they had been through to prepare themselves for the coming event.

I spent most of my time in the hospital, where I am sorry to say I had to leave my chum Terry, and the Section leader, Corporal Wilson. The rest of the time I put in looking after the Section that I had so unexpectedly had to command during the operations. About 10pm the “Ionian” stopped, the men were served with a hot meal to put them back in good humour, which consisted of bully beef stew: it went down well, and seemed to put fresh life into the men. At midnight, the two Destroyers that accompanied us came alongside, and the troops, who were all ready, began to embark on the black objects that were to carry them so close to the foe whom they had been so anxious to come to grips with. Everything was carried out without a hitch, and both military and naval personnel deserve great credit for same. It was not long before the Destroyers, their decks crammed with human freight, began to glide away from the transport. As soon as the other transports reached the same spot, they also went through the same performance. Everything was carried out in the utmost silence, and the officers were very pleased with their “boys”. The moon was up, and it was evidently brighter at that hour than was anticipated, for they decided to reduce the speed until it grew darker, so that we could approach closer to the shore without disturbing the Turks too soon.

It is hard to describe our short trip on the Destroyer, I will never forget it as long as I live, it is impossible for anyone who did not take part to realize what a grim sight it was to see so many black objects gliding so stealthily through the still waters. Not a light to be see, no voice was heard except that of the Commander of the Destroyer, and then it was inaudible a couple of yards away, and had to be conveyed to the different members of the crew by a couple of their own men detailed for the purpose. Soon after we embarked on to the Destroyer, we took off our packs and put them in readiness. The crew gave us all a good drink of cocoa, it was absolutely the best I had ever tasted; they were a fine lot of chaps and could not do enough to make the men comfortable in their rather cramped position, for there is not much space aboard these Destroyers at any time, so that you can draw your own conclusions as to what would be left after five hundred men had been strewn over their decks, roughly 250 each. Between two and three am, a very unfortunate accident occurred. One of the crew was attending to some gear in the stern, when somehow or other he over-balanced and splash in to the briny he went. “Man Over-board” was passed quietly along, the Destroyer at the same time was going a tidy pace; her speed slackened, and we soon realised that he was to be left to his fate, that his life was sacrificed for the sake of those on the Destroyer. It was hard to think of him struggling there alone, and yet we were all helpless. They said he was a splendid swimmer, and that they might pick him up the following day. He had my best wishes, and I would like to know if he was picked up, and one will be more happy and pleased than I if God spared him from a watery grave. There’s no doubt few people realize what “great lads” our tars are, they would give everything, even their life, to help the boys in Khaki, who, I am sure will never forget them after the war is over, and I daresay by that time, those people prejudiced against the boys in blue will realize what a wrong impression they have, and will in future give them what is due to them more credit in every respect.

Well, I’m getting off the track, so will get back again. The sadness that spread over the men through the previous account of the accident had barely died away, when another accident happened. This time it was our boys who were concerned. I was not near enough to witness the accident, but I have it from one who did, and I am prepared to take his version as correct as is possible to get under such unforeseen circumstances. The word had been passed along to put our gear on. The Destroyer was going slightly zig-zag and was slowing down at the time. We then knew that our grim journey was nearly over, and that it was “dinkum” (as the boys called it) at last. The rowers that had been told off to get into the boats which had been towed by transport, took their places, and one boat was practically filled with troops when the accident occurred. The Destroyer was still on a zig-zag course, and was trying to work herself into a good position. One tow rope was shorter than the other, and when the Destroyer swung around, the rear boat crashed into the boatload; the men shifted when they saw what was going to happen, that settled it, and over she went. I never want to hear the likes of it again, the shrieks and moans were terrible, I don’t know, nor does anyone else, how many were drowned. I believe the Destroyer’s crew were responsible for saving a good many of them. Whilst this sad drama was going on, I could see boatloads of men making a dash for the shore from all directions then when the boats were within about 25 yards of the shore, and before any of our men had time to get downhearted about their comrades’ unfortunate fate, one solitary shot rang out; a slight pause, and then another dozen. Then it started with a vengeance, the whole cliff seemed to be spitting bullets.

It was just breaking dawn when we steamed in, and it was not until we got fairly close that we had any idea that such a cliff was waiting for us; it was enough to take one’s breath away to think of having to climb it, to drive an enemy out of such a position seemed impossible, in fact madness to have such a cheek to attempt it. Anyway, the instructions were that it had to be done, and I will now do my best to tell you how it was done. Although the unfortunate accident cast a gloom over the men, they were not long in realizing that they were required to help clear the cliff, and with curses which are excusable in such a position, they entered the boats with a determination to make the Turks pay dearly. We were on the Destroyer “Foxhound”, and hardly began to disembark before we had to contend with not only rifle fire, but schrapnel [sic] also. Hell! I’ve never been in such a position in my life, rifle bullets whistling around us. Some w, worse luck, found a lodging place in some of our poor lads, whilst others would pass and enter the water with a “ping”, or bang against some part of the boat. The schrapnel soon found us and would explode right over our heads, but fortunately the enemy’s elevation was high and the lead was what they call “spent” by the time it hit us. They would give us a few more shells, then pause, then another batch, and so on. I thought I was a goner once, the shell burst with a terrific roar, and then I thought someone had struck me on the shoulder with a sledge-hammer. It was that number that I felt it was half blown off, and I said to my chum “that got me”. Gradually I got the use of it again, and was delighted when I found no blood was flowing. When I was getting into the bunk of the hospital ship that night, had a look at my shoulder and found a big black patch; by jove! I was lucky the schrapnel ball was a spent one, and then again can thank the strap of my equipment for doing it’s bit towards saving me.

It was not long before I had my section in a boat and making for terra firma. To be cooped up on a Destroyer, which has no shelter and be shot at without being able to retaliate, is deadly. In fact, I cannot imagine a more maddening position, but the men behaved admirably, and they swore that they would make up for it presently. After I had made sure that all my Section were in the boat, I made a dart for it, and in doing so, had to step over several comrades, one whose face I will never forget; poor chap, he was drilled right through, and I’m sorry to say, done for. The Naval men displayed their usual coolness, and took as much notice of the lead as would of a snowball. Several of them were wounded, whilst others donned the khaki and sneaked ashore and joined us, hey are a plucky lot no doubt. The boat I was in got ashore without anyone getting shot, but by jingo, I don’t know how it was managed. Bullets were whistling all around the boat, schrapnel was bursting in all directions, and yet we got through, marvellous. Just as my boat neared the shore, hearty cheers began to ring out, and upon looking up we saw what they were for. The Turks were cutting for their lives, and were just disappearing over the top of the cliff. Thinking we were near enough, I hopped out of the boat, and instead of the water being as I expected about up to my knees, I was surprised to find myself over waist deep. It was icy cold, and I did not take long to flounder ashore. Major Smith was waiting for his men, but it was a case of waiting for no orders; each man as soon as he reached shore, relieved himself of his pack, charged his magazine, fixed his bayonet, and was off.

Several boats were unlucky; in some cases not a man was able to land. My Section kept fairly well together and all made for the one spot, and all would have been well had schrapnel [not?] scattered them. Got most of them together again, and set off to scale the cliff, at the same time, all had to keep an eye open for Turks, especially the snipers. It was absolutely the stiffest climb I ever took no, it was thick with small bushes and the undergrowth gave us a good deal of trouble. At times, it was so steep that the men had to pull themselves up by shrubs, which method alone was responsible for several accidents. They would get half up when their supports snapped, and they would find themselves several yards down the cliff, with ether a sprained knee or ankle. I was in pretty good nick, but when I got to the top of the cliff I was that blown that I doubt if I could have used my rifle had it been necessary. I was first up out of my Section, most of the others were not long in joining me. They were all “up the spout”, all had a spell and then began to move forward. How we got up as far as we did without being “pinged” I don’t know, and another thing that beats me is, how as it the Turks gave up such a splendid position so quickly, everything was in their favour. I’ll guarantee they could not got our boys out of a like position at all, perhaps it was on account of the presence of the Naval forces that they quitted so hurriedly. Be that as it may, I am convinced that it was due to the way the boys tackled their task. After leaving the cliff, our advance was rapid.

About eleven o’clock, things were getting a bit brisk, and progress was not so fast. At this stage we were about two and half miles in and working our way towards the firing line. Before I proceed further, I had better explain that my Coy . was reserves, it was a s bad as being copped up on the boat because we could not get into the firing line as it was full up, so we had to just creeping froward, and take our chances of getting passed out without a chance to get some of our own back. It was here that the Turks began to give us “hell” with schrapnel, they had our range to a nicety, and for the next half mile they were bursting over us. Here the reserves were held up, they were just behind the firing line waiting to get in. We were losing heavily through this hail of schrapnel, and it was terrible to see so many getting bowled over, then the word was passed that we were going to advance. I was lying between my Platoon Commander and Roy Scobie (of my Section) at the time, then it came. I was half up when I stopped one, I gave my rifle a cant upwards, but quicker than it takes to tell, it was dashed out of my hand again, my hand was knocked behind me, at first I was afraid to look at it. I made sure my hand had been shot clean away; I can tell you I was relived when I found I got off so lucky, and I can undoubtedly thank my rifle for saving my thumb. The schrapnel struck the leaf of the backsight, and then glanced into my hand. It was jolly painful and I lost a terrible amount of blood. I told Roy Scobie that I was hit and promptly bandaged my wound up. It was hard luck to get passed out so early, but I could not pick and choose.

The next task I had to face was getting back to the beach; the schrapnel was sweeping the ground all the way. I cannot make out why I was not riddled amid such a hail of lead; it was like half a dozen hells having a go at each other. Snipers tried to get me, but I adopted a zig-zag rushing tactic, and reaching the beach safely, but was done to a dinner.

It was about noon when I was shot. I was simply astounded at the way our boys behaved under fire, I did not see one case that I was ashamed of, they were like our Naval men, and one would have thought they were doing their usual practice, the only difference was that more “ginger” was infused into their work on this occasion. They simply took no notice of the lead, all they wanted was to get at them with cold steel. I never thought they would have been so fond of the bayonet. The Army Medical Corps and stretcher-bearers displayed equal courage in carrying out their work, and I’m sorry to say suffered heavily.

I will never regret enlisting in the First Division, and to say I’m proud to belong to the Third Brigade is to put it very mildly indeed. One of the first thoughts that passed through my mind when I jumped into the water to land, was a picture that figured in our old school books entitled “The Landing of the Romans”, when their leader also jumped into the briny with is standard and crying “follow me” – never thought then that I would ever see a similar landing. War is a silly game, but I suppose they have to make room somehow.

I did not have to wait long on the beach. The Medical dressed my hand, ad I was able to catch a boat that was just leaving for the hospital ship “Gascon”, went to bed at once. My wound was bathed, I tried to sleep but it was no good, the pain was awful, and I had to have injections to ease the pain. This lasted for three days, after which it was less painful. The Sisters and all that were connected with the “Gascon” did all that was possible to relive the sufferings of the wounded. We arrived at Alexandria in the early hours of Thursday morning, disembarked and left there by training at 12.30pm, arriving at Heliopolis Hospital at 4.30pm. The next day, most of us were transferred to Mena. I have already supplied you with the particulars of my stay there, and I hope you received them safely. Of course, there is a great deal more that I could write about, but time will not permit. I think I have mentioned the main facts. I’m satisfied that when I thought I could realize what war was like, I was a long way out, one must go through it to find out.

Have not heard of R. Scott or Fred Contencin. R. H. Smith is a Colonel now, and in charge of the Battalion and is still going strong. I only wish I had been able to dodge ‘em a few days, it would have given me a chance of promotion. Well, it’s no use growling, I will have another chance, and I ought to consider myself lucky and I certainly do. The Third Contingent are gradually putting in an appearance, they will wonder what they have struck when they get here, the heat is terrible, and 120 in the shade is nothing out of the ordinary. It is not right to put men under canvas at this time of year.

There have been a good many cases of sunstroke among different troops in Egypt, some fatal. Frank Elliot, who lives at Crescent met me the other night, he said Mrs. Stump told him to look out for me. My thumb is still weak and sore, but I’m hoping to be on my way back in a few days. I’m not going to stay here any longer, and I will send a few lines later to let you know why. My health his OK, although I have not an ounce of grease on me, and if I stayed here much longer, I would just about be reduced to a frame. I hope you will be able to make something out of this letter, I have had to write it at intervals, and I find it rather disconcerting to have so many interruptions, so please overlook etc. No Letters received yet, it’s enough to make one sick, just fancy, over eight weeks since I received the last. Give my kind thoughts and best wishes to all friends and pals. Hoping this will find you all in the best of health and spirits, and trusting to hear from you soon. Will close now, with fondest love and kisses to all.

From

Bill

William Keats transferred to the 52nd Battalion on its formation on 1/3/1916, was appointed 2nd Lieutenant on 24th May 1916 and to Lieutenant on 28th August 1916, thus getting his wish for promotion. On 29th October 1916 he was posted for duty to the 13th Training Battalion, serving part of his time at the Grenade School at Clapham Common. He returned to the 52nd Bn on 24th April 1917. He died of wounds received in action at the battle of Messines on June 16th 1917. Lt Wilson (56th Bn at the time of the statement) gave the following statement, recorded in the Red Cross file:

“Lieut Keats was talking to me about 10pm on 19th June 17. We were waiting to advance at 10.5pm. The enemy were shelling heavily. A shell hit within a couple of yards of us and he fell into my arms. He had been wounded in his thigh, but I thought that the piece had penetrated. I bound him up and as the time had come to push on, I left my batman Pte Gaffney with Lt Keats.

He reported to me about 20 minutes later saying that Lt Keats had died. That was at Sheet 28 S.W. O.33.b.84 just on the road at that point. I do not know if he was buried there, but a burying party under Lt B Hart, 49th Battalion, went over that area.

(Sgd) B Wilson. Lieut.

56th Battalion AIF

A letter was later sent to the family reiterating these details. A big thanks to Dorothy Figg for supplying this material.